|

| By permission of the Wisconsin Historical Society |

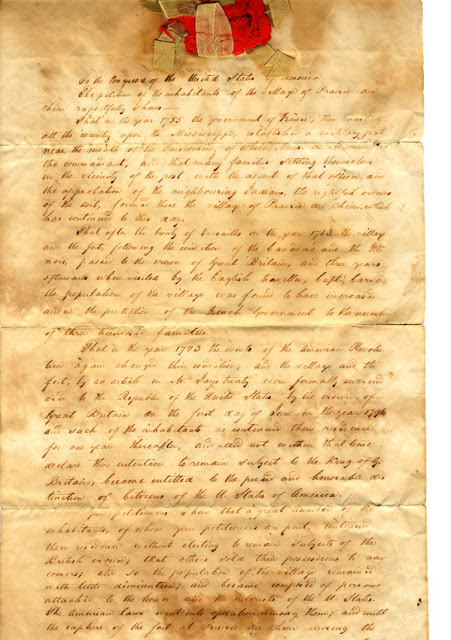

The above document was composed at Prairie du Chien in 1816 and was donated to the Wisconsin Historical Society in 2010 by the descendants of one of the petitioners to Congress named in writing. It is supposed to be in the hand of John W. Johnson, fur trader, one of the few persons at Prairie du Chien who could write well in the English language in that year. The rest were French speakers. 54 individuals, mostly making their marks, asked Congress to award them legal title to their lands and homes, as their fathers or grandfathers had been settlers since 1755. In addition to its historic significance, the document should be helpful to genealogists, as it attests to certain parties being residents as early as 1816, at least. The rest of the pages of the petition, in remarkably fine condition for its age, a transcription and more information in the form of a description can be seen on the society's website at

http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/cdm4/document.php?CISOROOT=/tp&CISOPTR=72462&CISOSHOW=72455

I