As explained in another post, below, I had recently begun to suspect that the diary of Father Lucien Galtier had not been lost, despite what Dr. Peter Scanlan wrote in 1929 regarding the item. Therefore, on a visit to St. Gabriel's Church of Prairie du Chien, WI, the last parish of Galtier, I decided to do a search. After a look through a number of very old ledgers kept in a cabinet, I finally came upon what may be the remnant of the journal of the priest, but not exactly as described by Scanlan. This was last Friday and the office was about to close. I had to leave PdC on Sunday, to my immense frustration, and have had no more chance to study what I found, except the three pages I copied. Probably only someone like myself, who is able to instantly recognize the handwriting of Lucien Galtier, could have known the significance of the bound journal, depicted at left--for the very reason that so little remains of it. The label pasted on the cover is not original. The writing upon it is not in Galtier's hand and says "Interesting old records from 1840, 1857, etc." Whatever this is, the actual diary of Lucien Galtier, described by Dr. Scanlan, or another-- it definitely belongs to the time of his pastorate. Dr. Scanlan having written, "It [the journal] consists of a clear statement of business matters pertaining to St. Gabriel's Church largely..." both makes it very difficult to know if the book, depicted above, is the one he referred to and yet guarantees that it can be because the pages I saw are merely that--business matters pertaining to St. Gabriels and the residence of the priest. I do not think that St. Gabriel's had any separate account books in those days because it had no office staff. Since this journal also pertains to expenditures for the house of Father Galtier, which belonged to him and not to the church, it must have been the property of the priest--just as was the one of which Peter Scanlan wrote.

As explained in another post, below, I had recently begun to suspect that the diary of Father Lucien Galtier had not been lost, despite what Dr. Peter Scanlan wrote in 1929 regarding the item. Therefore, on a visit to St. Gabriel's Church of Prairie du Chien, WI, the last parish of Galtier, I decided to do a search. After a look through a number of very old ledgers kept in a cabinet, I finally came upon what may be the remnant of the journal of the priest, but not exactly as described by Scanlan. This was last Friday and the office was about to close. I had to leave PdC on Sunday, to my immense frustration, and have had no more chance to study what I found, except the three pages I copied. Probably only someone like myself, who is able to instantly recognize the handwriting of Lucien Galtier, could have known the significance of the bound journal, depicted at left--for the very reason that so little remains of it. The label pasted on the cover is not original. The writing upon it is not in Galtier's hand and says "Interesting old records from 1840, 1857, etc." Whatever this is, the actual diary of Lucien Galtier, described by Dr. Scanlan, or another-- it definitely belongs to the time of his pastorate. Dr. Scanlan having written, "It [the journal] consists of a clear statement of business matters pertaining to St. Gabriel's Church largely..." both makes it very difficult to know if the book, depicted above, is the one he referred to and yet guarantees that it can be because the pages I saw are merely that--business matters pertaining to St. Gabriels and the residence of the priest. I do not think that St. Gabriel's had any separate account books in those days because it had no office staff. Since this journal also pertains to expenditures for the house of Father Galtier, which belonged to him and not to the church, it must have been the property of the priest--just as was the one of which Peter Scanlan wrote.To my great sadness, most of the pages of the journal had literally been ripped out, their stubs still visible. The cover is in rather good condition [click on images to enlarge] but it is doubtful that it ever contained about 340 pages, as Scanlan had estimated. I was able to examine a very similar [probably the very same type, judging by the stripes on the cover] volume from the same era at the Villa Louis of Prairie du Chien and the page count is more like 240. The first thing I did, upon recognizing the penmanship of the priest, was to look in the back of the book for the list of wild flowers that Scanlan noted Father Galtier had compiled. They were not there. Because of time constraints, I was not able to actually count how many pages remain in the journal today but I would be surprised if ten managed to survive the wanton desecration of this account book at some point in time--and two of them were not even written by Lucien Galtier. My guess is that all the "interesting parts", whatever they may have been, were removed for whatever motive. I only had time to take photos of or photocopy a few of the pages, one of them being the image below:

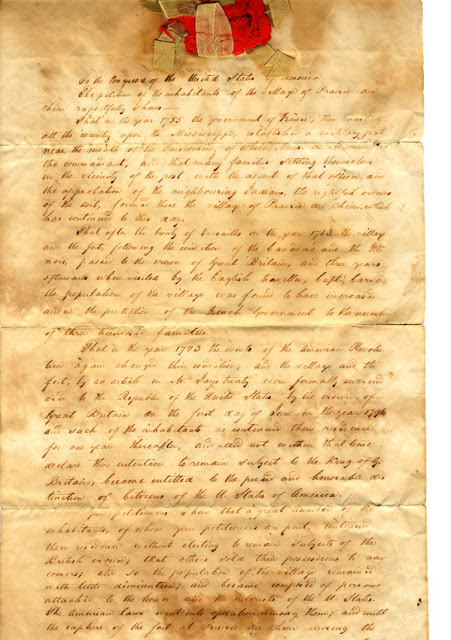

The page at left has the heading at the very top [in French] "Expenditures for the church and the rectory of Prairie du Chien--1857. " But the rest is in the hand of Father Jean Claude Perrodin, who was filling in at St. Gabriel's from September of 1857 to May of 1858. [The entries of the expenses paid alternate, for some reason, between English and French, the languages in which Perrodin was fluent.] Below that, written in English and heavily crossed out are the words: "Debt of the church (the ,,,of 170.00) or more [something added in French and then inked over] =$85. Due by the .....to Mr, Galtier or by Mr. Galtier to his successor." I could not make out all the words yet but experience has taught me that they may become clear later. Galtier is referred to as both "Mr." and "father" in this section, which was perfectly correct for the time. In 1857 Father Galtier took a trip to Europe and was not quite certain of staying at Prairie du Chien, evidently. The reason for this is known to me but does not warrant explanation here. Galtier stayed on. All that was written and deleted does not make the most sense but why someone Xed-out the entire summary at the top is a mystery. The disbursements for 1857 are quite mundane, mostly for building materials, but the first one for 1858 is the interesting "March 18- paid to Mr. Kissner for playing the Melodeon-$10." Ten bucks was quite a lot of money in 1858 and another page clarifies that it was for two months worth of playing, but it's not clear whether the Melodeon involved was an organ or an accordion.

Another page continues the total spent on the church and the priest's house up to May 26, 1858. On May 28th, Father Perrodin signed the page of the journal, verifying that the sum of $172. had been received by the substitute priest "from L. Galtier", this last part added as an afterthought in the hand of Galtier. [in fact Peter Scanlan mentioned "All Father Galtier's signatures are simple 'L. Galtier'"] Thus ends the recordings of Jean Claude Perrodin. [In 1866 Perrodin conducted the funeral of his colleague.] Farther down, on the left hand side is a list of names of individuals in the penmanship of Galtier. They are mostly Irish, followed by numbers of unknown significance and, on the right, there is a "wine bill" expense such as that mentioned by Scanlan and money spent on other things, like candles, jotted down in pencil. [Please do not copy the images in this post without my consent. They were taken by me and therefore I own the rights to them.] Due to all its missing pages, the journal was being used as a kind of "folder" for various letters and documents, some of them very interesting, indeed, and of equal antiquity to and older than the remaining entries of J. C. Perrodin and Lucien Galtier, including a letter written to him from Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1861. There is also a deed for land written by Galtier.